All operations produce products and services by changing inputs into outputs using an ‘input-transformation-output’ process. Figure 1.3 shows this general transformation process model. Put simply, operations are processes that take in a set of input resources which are used to transform something, or are transformed themselves, into outputs of products and services. And although all operations conform to this general input–transformation–output model, they differ in the nature of their specific inputs and outputs. For example, if you stand far enough away from a hospital or a car plant, they might look very similar, but move closer and clear differences do start to emerge. One is a manufacturing operation producing ‘products’, and the other is a service operation producing ‘services’ that change the physiological or psychological condition of patients. What is inside each operation will also be different.

The motor vehicle plant contains metal-forming machinery and assembly

processes, whereas the hospital contains diagnostic, care and

therapeutic processes. Perhaps the most important difference between the

two operations, however, is the nature of their inputs. The vehicle

plant transforms steel, plastic, cloth, tyres and other materials into

vehicles. The hospital transforms the customers themselves. The patients

form part of the input to, and the output from, the operation. This has

important implications for how the operation needs to be managed.

Inputs to the process

One set of inputs to any operation’s processes are transformed resources. These are the resources that are treated, transformed or converted in the process. They are usually a mixture of the following:

One set of inputs to any operation’s processes are transformed resources. These are the resources that are treated, transformed or converted in the process. They are usually a mixture of the following:

● Materials – operations which process materials could do so to transform their physical properties (shape or composition, for example). Most manufacturing operations are like this. Other operations process materials to change their location (parcel delivery companies, for example). Some, like retail operations, do so to change the possession of the materials. Finally, some operations store materials, such as in warehouses.

● Information – operations which process information could do so to transform their informational properties (that is the purpose or form of the information); accountants do this. Some change the possession of the information, for example market research companies sell information. Some store the information, for example archives and libraries. Finally, some operations, such as telecommunication companies, change the location of the information.

● Customers – operations which process customers might change their physical properties in a similar way to materials processors: for example, hairdressers or cosmetic surgeons. Some store (or more politely accommodate) customers: hotels, for example. Airlines, mass rapid transport systems and bus companies transform the location of their customers, while hospitals transform their physiological state. Some are concerned with transforming their psychological state, for example most entertainment services such as music, theatre, television, radio and theme parks.

Often one of these is dominant in an operation. For example, a bank devotes part of its energies to producing printed statements of accounts for its customers. In doing so, it is processing inputs of material but no one would claim that a bank is a printer. The bank is also concerned with processing inputs of customers. It gives them advice regarding their financial affairs, cashes their cheques, deposits their cash, and has direct contact with them. However, most of the bank’s activities are concerned with processing inputs of information about its customers’ financial affairs. As customers, we may be unhappy with badly printed statements and we may be unhappy if we are not treated appropriately in the bank. But if the bank makes errors in our financial transactions, we suffer in a far more fundamental way. Table 1.3 gives examples of operations with their dominant transformed resources.

The other set of inputs to any operations process are transforming resources. These are the resources which act upon the transformed resources. There are two types which form the ‘building blocks’ of all operations:

● facilities – the buildings, equipment, plant and process technology of the operation;

● staff – the people who operate, maintain, plan and manage the operation. (Note that we use the term ‘staff ’ to describe all the people in the operation, at any level.)

● facilities – the buildings, equipment, plant and process technology of the operation;

● staff – the people who operate, maintain, plan and manage the operation. (Note that we use the term ‘staff ’ to describe all the people in the operation, at any level.)

The exact nature of both facilities and staff will differ between operations. To a five-star hotel, its facilities consist mainly of ‘low-tech’ buildings, furniture and fittings. To a nuclearpowered aircraft carrier, its facilities are ‘high-tech’ nuclear generators and sophisticated electronic equipment. Staff will also differ between operations. Most staff employed in a factory assembling domestic refrigerators may not need a very high level of technical skill. In contrast, most staff employed by an accounting company are, hopefully, highly skilled in their own particular ‘technical’ skill (accounting). Yet although skills vary, all staff can make a contribution. An assembly worker who consistently misassembles refrigerators will dissatisfy customers and increase costs just as surely as an accountant who cannot add up. The balance between facilities and staff also varies. A computer chip manufacturing company, such as Intel, will have significant investment in physical facilities. A single chip fabrication plant can cost in excess of $4 billion, so operations managers will spend a lot of their time managing their facilities. Conversely, a management consultancy firm depends largely on the quality of its staff. Here operations management is largely concerned with the development and deployment of consultant skills and knowledge.

Outputs from the process

Although products and services are different, the distinction can be subtle. Perhaps the most obvious difference is in their respective tangibility. Products are usually tangible. You can physically touch a television set or a newspaper. Services are usually intangible. You cannot touch consultancy advice or a haircut (although you can often see or feel the results of these services). Also, services may have a shorter stored life. Products can usually be stored, at least for a time. The life of a service is often much shorter. For example, the service of ‘accommodation in a hotel room for tonight’ will perish if it is not sold before tonight – accommodation in the same room tomorrow is a different service.

Although products and services are different, the distinction can be subtle. Perhaps the most obvious difference is in their respective tangibility. Products are usually tangible. You can physically touch a television set or a newspaper. Services are usually intangible. You cannot touch consultancy advice or a haircut (although you can often see or feel the results of these services). Also, services may have a shorter stored life. Products can usually be stored, at least for a time. The life of a service is often much shorter. For example, the service of ‘accommodation in a hotel room for tonight’ will perish if it is not sold before tonight – accommodation in the same room tomorrow is a different service.

Most operations produce both products and services

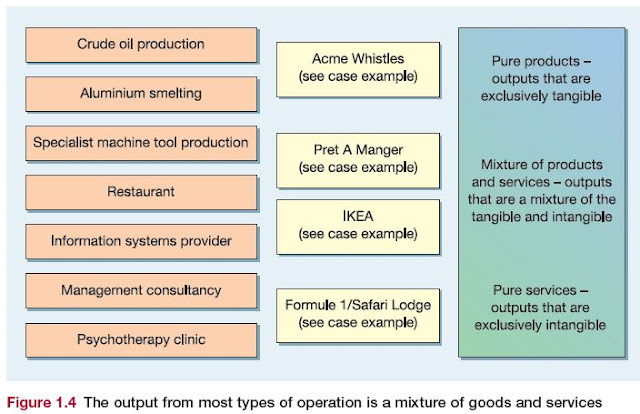

Some operations produce just products and others just services, but most operations produce a mixture of the two. Figure 1.4 shows a number of operations (including some described as examples in this chapter) positioned in a spectrum from ‘pure’ product producers to ‘pure’ service producers. Crude oil producers are concerned almost exclusively with the product which comes from their oil wells. So are aluminium smelters, but they might also produce some services such as technical advice. Services produced in these circumstances are called facilitating services. To an even greater extent, machine tool manufacturers produce facilitating services such as technical advice and applications engineering. The services produced by a restaurant are an essential part of what the customer is paying for. It is both a manufacturing operation which produces meals and a provider of service in the advice, ambience and service of the food. An information systems provider may produce software ‘products’, but primarily it is providing a service to its customers, with facilitating products. Certainly, a management consultancy, although it produces reports and documents, would see itself primarily as a service provider. Finally, pure services produce no products, a psychotherapy clinic, for example. Of the short cases and examples in this chapter, Acme Whistles is primarily a product producer, although it can give advice or it can even design products for individual customers. Pret A Manger both manufactures and serves its sandwiches to customers. IKEA subcontracts the manufacturing of its products before selling them, and also offers some design services. It therefore has an even higher service content.

Some operations produce just products and others just services, but most operations produce a mixture of the two. Figure 1.4 shows a number of operations (including some described as examples in this chapter) positioned in a spectrum from ‘pure’ product producers to ‘pure’ service producers. Crude oil producers are concerned almost exclusively with the product which comes from their oil wells. So are aluminium smelters, but they might also produce some services such as technical advice. Services produced in these circumstances are called facilitating services. To an even greater extent, machine tool manufacturers produce facilitating services such as technical advice and applications engineering. The services produced by a restaurant are an essential part of what the customer is paying for. It is both a manufacturing operation which produces meals and a provider of service in the advice, ambience and service of the food. An information systems provider may produce software ‘products’, but primarily it is providing a service to its customers, with facilitating products. Certainly, a management consultancy, although it produces reports and documents, would see itself primarily as a service provider. Finally, pure services produce no products, a psychotherapy clinic, for example. Of the short cases and examples in this chapter, Acme Whistles is primarily a product producer, although it can give advice or it can even design products for individual customers. Pret A Manger both manufactures and serves its sandwiches to customers. IKEA subcontracts the manufacturing of its products before selling them, and also offers some design services. It therefore has an even higher service content.

Formule 1 and the safari park (see later) are close to being pure services, although they both have some tangible elements such as food.

Services and products are merging

Increasingly the distinction between services and products is both difficult to define and not particularly useful. Information and communications technologies are even overcoming some of the consequences of the intangibility of services. Internet-based retailers, for example, are increasingly ‘transporting’ a larger proportion of their services into customers’ homes. Even the official statistics compiled by governments have difficulty in separating products and services. Software sold on a disc is classified as a product. The same software sold over the Internet is a service. Some authorities see the essential purpose of all businesses, and therefore operations processes, as being to ‘service customers’. Therefore, they argue,

all operations are service providers which may produce products as a part of serving their customers. Our approach in this book is close to this. We treat operations management as being important for all organizations. Whether they see themselves as manufacturers or service providers is very much a secondary issue.

all operations are service providers which may produce products as a part of serving their customers. Our approach in this book is close to this. We treat operations management as being important for all organizations. Whether they see themselves as manufacturers or service providers is very much a secondary issue.